The French philosopher Jean Buridan (1300-1358), Ockham’s disciple, is attributed the following paradox: with a hungry ass at exactly equal distance from two stacks of hay of the same size, weight and shape, what decision will he make? Which stack of food will it go to? According to the philosopher, the donkey would unfortunately die of indecision and hunger … It does not eat because it does not know, cannot or does not want to choose which stack is more convenient.

A similar problem is posed by Aristotle (384 BC-322 BC) in “On the Heavens”, where he wondered about what decision a man equally hungry and thirsty would make when faced with two tables, one full of food and the other full of drinks. For Aristotle, man would remain paralyzed.

In his writings Buridan didn´t discuss the issue, in his work he alludes to a psychological determinism, where the will remains free, with the freedom to do or not to do, to do this or that, as long as the understanding has not presented it with a more powerful motive to act.

Although I do not want to make this article a philosophical paper at all, the idea is to present decision-making as an important component in climbing, and even more so in climbing competitions, where time and the possibilities of resolution add an important value to obtain the best possible result.

A key factor in decision-making is the information we have and can perceive from the environment, in a previous article “What the climber’s eyes tell the climber’s brain“, based on the work of the Psychologist James Gibson about of perception and the taking of information from the environment I described some studies related to perception.

The biggest difference between climbers of different levels is in how much information they are able to attend, and, therefore, the availability of opportunities for action (affordances) to use or choose (Orth et al, 2016). These opportunities are closely linked to how much information I perceive, but mainly conditioned by three interdependent units called constraints: the environment, the task and the organism (oneself with its possibilities).

To get an idea, according to sports performance models, experts have greater perceptual capacity (anticipation, discrimination, recognition and recall of said information), greater attentional capacity (reproduction and automation of actions), cognitive capacity (representation of the problem and their solutions) and greater motor capacity (automaticity of the necessary movement patterns) (Ruiz Perez and Arruza Gabilondo, 2005).

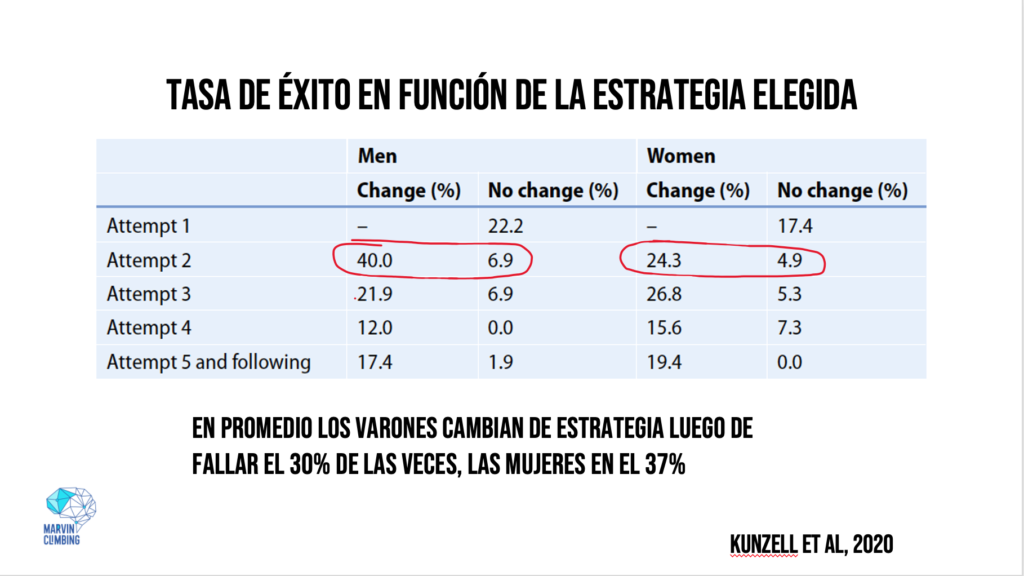

Take the case of the Boulder competitions, Kunzell et als (2021) studied the performance of the finalists of the 2017 Boulder World Cups. They distinguished how athletes act after a failed first attempt, who kept their strategy, or who took the decision to change. The table below clearly shows that the success rate when changing solutions is substantially higher than repeating the previous solution.

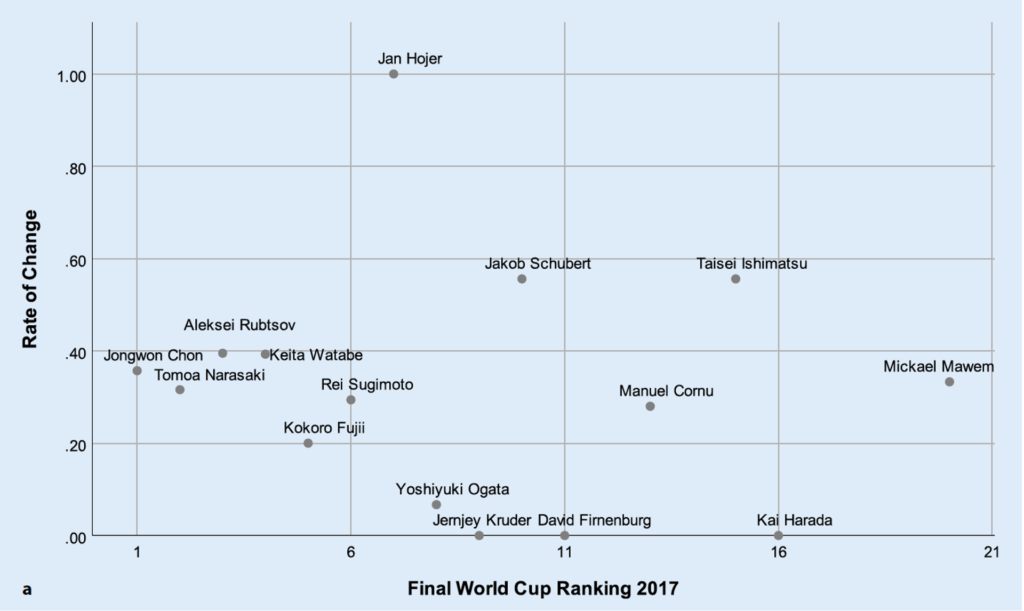

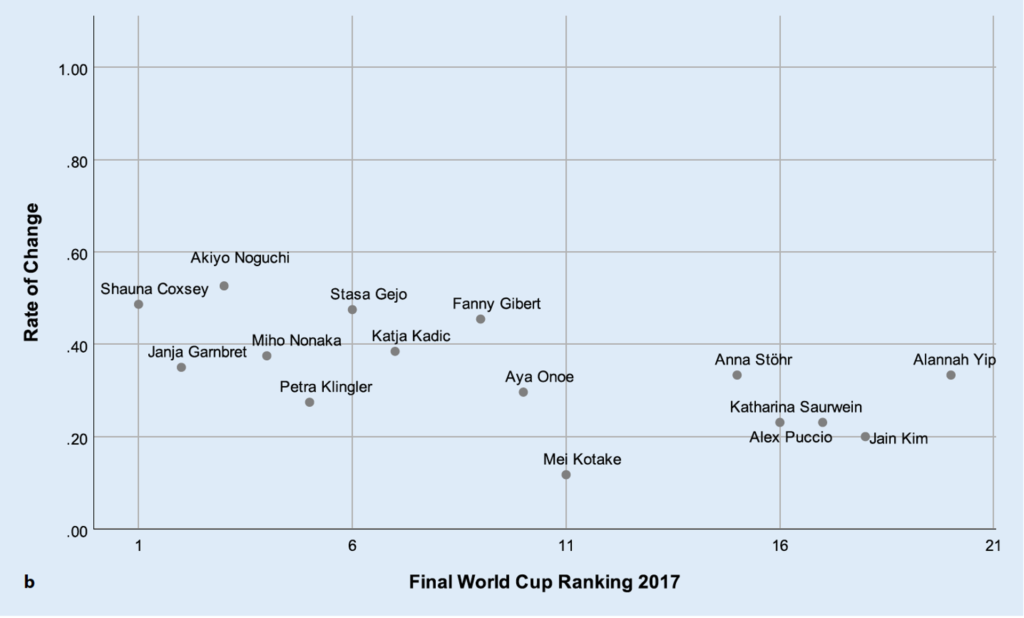

Furthermore, they found a correlation between the frequency of finding new solutions and the final position in the ranking. In the following tables we can see this correlation in both male and female athletes.

From this study it is concluded that while men change the strategy after failing 30.4% of the time, women do so after failing 37.7%. Beyond that the success rate is much higher when changing solutions than when they remain firm in a particular solution. The authors recommend that athletes should learn to correctly evaluate the probability of success of a certain strategy once they have tried and failed, and should always practice developing new strategies for the same Boulder problem.

Looking for options before the first attempt, or immediately after it, is an essential characteristic for success in Boulder competitions, as is knowing how to make the right decision about when to change strategy to obtain a better score.

Of course, the decisions that are optimal for one climber do not have to be for another, even if they are climbers of the same level and in the same competition, have the same information and adopt a similar criterion for their respective decision-making.

There are several reasons for the two climbers to make different decisions. In the first place, its morphological and physiological characteristics, its motor repertoire, the tastes, preferences, or styles that a climber has to face each problem. Another factor may be the risk position that each one has, which will make your decision more conservative, focusing on the solution that you feel comfortable with. There are people much more risky than others when it comes to taking risks with new or creative solutions.

Although decision-making in sport is highly studied, mainly everything that is written emphasizes opposition situations and a variable environment, in short periods of time, some analyzes can help us understand this phenomenon that, as we have seen, seems to be decisive .

For the expert athlete, the sources to collect information are diverse, firstly, he must manage the information about the environment (affordances), secondly, he must process the information about himself and his personal state, as well as about his own motor response, that is say the organization of the nerve impulses required for the performance of the movement and its result. Without leaving aside the feelings and moods. Which leads to the conclusion that there are different cognitive and emotional levels that influence decision-making (Ruiz Perez and Arruza Gabilondo, 2005)

In many circumstances the athlete can use previous schemes, situation-decision-action configurations, which he has stored, in which the previous situations worked, but in others he must elaborate a new situation, since it does not resemble the known or not at all it fits into the scheme it dominates, thus generating a novel emerging behavior or action.

Already in 1935 Nikolai Bernstein incorporated the notion of engram as a precursor of the movements stored in memory: these engrams represent the topology of the movements, but it does not suppose which forces should be carried out, which muscles to activate or other variables (Latash, 2015).

Anticipation plays a key role, both at the level of coordination (the production of the net mechanical effect, such as muscular forces, torques, displacements, etc.) or at the level of control (without any obvious mechanical effect but that modifies the state or trajectory in anticipation of future action).

The model proposed by Memmert (Medernach and Memmert, 2021) gives us a basis to understand the cognitive processes that underlie this key phenomenon in climbing boulder problems. The first thread consists of the anticipation of the task; In the next one, the athlete perceives the stimulus through visualization, obtaining all the necessary information, especially its movement demands and comparing it with the stored movements (engrams), for in the last it generates possible resolutions and chooses the most appropriate one. These last two tasks are decisive when facing a Boulder problem in a competition, since the possible solutions and their corresponding choice will be the keys to staying within the aforementioned parameters: having several options and managing them to achieve the greatest efficiency and therefore the best result.

The best solution, as we mentioned before, will depend on the personal characteristics and specific abilities of each individual, which are always integrated in decision-making, often generating a tendency to monotony in the chosen solutions, avoiding creative and riskier solutions.

When a problem presents itself, intuitive thinking quickly tries to solve it. If the climber recognizes the situation as familiar, he generally makes the decision quickly to solve in a certain way, but when the information obtained is not enough, or confusing and the problem presented has a high level of complexity, if we let intuitive thinking act , will fall into what is called an intuitive heuristic, that is, when we find ourselves in a difficult situation, we often respond with an easier one, usually without realizing the situation (Kahneman, 2011)

In this sense, in the book ¨Think fast, think slowly¨ by the Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, he suggests that decisions can be made by one of the following two systems: system 1, quick and intuitive thinking, with little or no no effort and no sense of voluntary control, and system 2, which focuses on mental activities, which require conscious effort, and above all it is not immediate, but the author himself calls it a slow system.

Many times the search for an intuitive solution fails, no expert solution or heuristic answer comes to mind. In these cases is when system 2 begins to act processing the information. What Kahneman with his research partner Tversky found is that System 1 is more influential than we think and is the author of many choices and judgments we make.

This system is very well described by Malcom Gladwell (2005) in his book ¨Blink: the power of thinking without thinking¨ about those instinctive thoughts, which solve a complex situation almost fortuitously without knowing why of that decision. Although spontaneous decisions can be as good as decisions made cautiously and deliberately, it is essential that we do not win the temptation to solve or seek solutions with system 1, but rather give it time and for system 2 to act, solving, Analyzing the situations to be able to make the best decision and look for other options that, as demonstrated in the bouldering world cups, would seem to be the key if the first option could not materialize.

The important thing is to form the habit of generating second opinions, options, solutions. Mainly forcing these situations in training will be the key to optimizing performance and being efficient in our performance. Working with colleagues, exchanging opinions and, above all, trying alternatives will generate Bernstein-style engrams that can later be valid alternatives for decision-making. As Adam Grant (2021) describes in his book Think Again, you have to think like a scientist, always look beyond the limits of your own understanding (of your own logic), doubt, be curious and update your knowledge of the situation based on new data or information that we may collect. Experimenting with all possible forms of movement for each situation.

One of the keys in this whole process is to play, to play with movement, to learn through the exploration of all the possible ways of solving a problem. Use divergent thinking that allows us to see connection outside of nature (or normality) and in this way find different solutions to certain problems. With activities planned as brainstorming, possible resolutions that are not within the possible logical resolutions can be found.

In the image on the left you can see the standard solution to a problem, and in the image on the right, you see a climber solving creatively due to his height. Could he have solved it?

Imagery, that is, the idea of thinking visually instead of doing it verbally, helps patterns emerge that are possible resolutions to the problems posed. The visualization of situations and resolution of those situations in the most varied way possible is one of the key aspects that should be stimulated in athletes. Part of the coach’s job is to generate that ability to mentally imagine and resolve the task to be performed.

Having more options does not mean generating a dilemma like that of the donkey, but it opens up a world of possibilities from which to choose according to the strategy that we have raised. In a competitive situation, we must evaluate their weight and the best one) that lead us to achieve the objective.

References:

Aristóteles (1996). Acerca del cielo; Meteorológicas. Biblioteca Clásica Gredos. Miguel Candel (trad.). Madrid

Gladwell, M., (2005). Blink : the power of thinking without thinking. New York :Little, Brown and Co.

Grant, A., (2021). Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know. Penguin Publishing Group.

Kahneman, D., (2012). Pensar rápido pensar despacio. Barcelona. Ed. Debate

Kunzel, S., Thomicsek, J., Winkler, M., Augste C., (2020). Finding new creative solutions is a key component in world-class competitive bouldering. Ger J Exerc Sport Res 2021 · 51:112–115

Latash, M. L. (2015). Bernstein’s “desired future” and physics of human movement. Cognitive Systems Monographs, 25, 287-299.

Medernach, J., Memmert, D., (2021). Effects of decision-making on indoor bouldering performances: A multi-experimental study approach. PLoS ONE, Vol. 16 Issue 5, p1-26. 26p.

Orth D., Button C., Davids K. (2016). What current research tells us about skill acquisition in climbing. En: The science and practice of climbing and mountaineering. Routledge

Ruiz Perez, L., Arruza Gabilondo, J. (2005). El proceso de toma de decisiones en el deporte. Clave de la eficiencia y el rendimiento óptimo. Barcelona. Ed. Paidós Ibérica

Spinoza, B. (2011). Ética: demostrada según el orden geométrico. Alianza Editorial.

Leave a Reply