¨Innovation, then, means finding new ways to apply energy to create improbable things, and see them catch on. It means much more than invention, because the word implies developing an invention to the point where it catches on because it is sufficiently practical, affordable, reliable and ubiquitous to be worth using.¨ Matt Ridley

The young Peter O’Brien, frustrated by not being able to exceed 18 meters in the shot put during his stay at the University of Southern California, dedicated his time to exploring new ways to propel the shot beyond that distance. Even in early hours of the morning on a neighboring field, he practiced different forms for a long time until he literally took a turn in the throwing technique. He positioned himself with his back to the circle, gaining a 180 degree turn to quickly bring the weight to the front of the circle optimizing momentum before unleashing the 16,000 pound bullet propelling it beyond its previous distances. The theory behind his launch in his own words: ¨the longer you push, the further the bullet will travel¨

Like any new technique, many doubted its usefulness, but it was not until the first records fell that the technique began to become popular under the name of O’brien Glide. Between July 1952 and June 1956 he won 116 consecutive victories, broke the world record 17 times, and was the first man to break the 18m and 19m barriers. He won gold at the 1952 and 1956 Olympics, silver in 1960, and in 1964 he placed 4th. His record was 19.64 meters.

Four years after O’Brien’s last participation, at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, Dick Fosbury changed the high jump technique forever. The young jumper surprised everyone in attendance by winning Olympic gold by applying a novel jumping technique. Instead of using the conventional techniques such as the scissors, or the straddle, the new technique consisted of running towards the bar in a curved path and with greater speed, so that the final approach is made in a transverse direction to the bar, to jump back to it., falling with the neck or shoulders.

¨I take off on my right, or outside, foot rather than my left foot. Then I turn my back to the bar, arch my back over the bar and then kick my legs out to clear the bar.¨

At the 1972 Munich Olympics, 28 out of 40 jumpers used this technique (unfortunately Fosbury did not qualify) and Seoul 1988 was the last time the Straddle technique was used, making it the only current technique. In Fosbury’s words: “I thought that after winning the medal, one or two jumpers would start using the technique, but I never really contemplated that it would become the universal technique.”

In relation to climbing, and in particular in the speed discipline, at the Asian Games 2018, the Boulder specialist Tomoa Narasaki in his duel with Chon Jong-won used a particular technique, the Tomoa Skip. This technique allowed skipping the 4th hold, obtaining a more direct trajectory, avoiding that excessive displacement to the left that forces the competitors to make a zigzag. Although in previous years the Iranian climber Reza Alipourshenazandifar used a similar strategy, the Tomoa skip was gaining popularity.

Given his history as a gymnast and his great skill in Bouldering, Tomoa Narasaki thus managed to rank among the best in this specialty, and achieving his place in the Tokyo Olympics, where obtaining a good result in this modality is of great importance for the final classification.

Such is the impact of the Tomoa Skip today that in Tokyo 2021, 6 of the 7 male finalists and 7 of the 8 female finalists used this technique, taking into account that there were no speed specialists in that final (except for the Polish Miroslaw who I don’t use the skip) and at the last World Cup in Salt Lake City, 14 of the 16 male and 12 of the 16 female finalists used the Tomoa Skip technique, establishing itself as a standard in the discipline, and has been used to break several times the speed record, such as that of the Indonesian climber Aries Susanti Rahayu when she under the 7-second barrier or her compatriots Leonardo Veddriq and Kiromal Katibin who smashed the record several times in the last three speed world cups 2022 leaving it at 5 ´10¨.

How is it possible that creative and innovative techniques emerge in sport?

According to Orth et al (2017), creative motor actions are functional movement patterns that are new to the individual or group and are adapted to satisfy the constraints of the motor problem. A creative behavior does not necessarily have to be novel for the entire population, but it can be novel for the individual himself.

Kaufman and Beghetto (2009) propose a structure for the acquisition of creativity in 4 levels:

Mini C: the novel and personally significant interpretation of experiences, actions and events (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2007). It is inherent to the learning process and generally manifests itself when the learner discovers a solution to a motor problem. It is the adaptation of known techniques to their personal conditions. It has a direct relationship between the learning process and creativity, since the individual must find/generate a unique solution for their possibilities. Consider a climber trying to solve a task

Little C: refers to the creative behavior that can be observed in athlete-environment interactions in amateur athletes, here the solutions are not from expert athletes but they will allow solving the problem, perhaps with a greater expenditure of energy than an expert.

Pro C: This behavior is defined by the emergence of patterns that can be found in athlete-environment contexts where the demand requires highly technical, flexible and integrated action. For example the creation of a novel solution to a problem within a Boulder competition.

Big C: they consist of the invention of a new efficient and functional technique that spreads quickly in the environment. Narasaki, Fosbury and O’Brien found themselves in this situation when searching for and creating the gesture they were inventing to solve the problem that was preventing them from progressing. Many times in these cases, the modifications of the rules (conditions of the task), the surfaces where the sport takes place (conditions of the environment), or the improvement of physical condition, or growth and/or maturation (conditions of the organism) allow the emergence of these creative actions.

Without the switch from the sandbox to landing mats in the high jump, jumping on his back and landing on his neck and shoulders would not have been an option for Fosbury. Tomoa Narasaky’s levels of agility and strength allowed the creation of the Skip, and anyone who has practiced it knows that a high level of strength, mobility and coordination is required to perform it.

These four levels should be seen as a process by which creativity develops. All Big Cs have their genesis in the mini Cs. Without proper stimulation of the lower level, the higher levels are unlikely to manifest.

Flexibility, variability and adaptability.

In dynamic systems, spontaneous pattern formation emerges through a process called self-organization. These systems are called open, where information from both the environment and the organism itself is constantly incorporated. This self-organization arises from the possibility that the organism has to solve the task in many ways. In the 1960s, Bernstein postulated the problem of the degrees of freedom that results from an infinite redundancy of degrees of freedom that exist to solve a motor task, for example and only at the joint level, in the arm we have 7 degrees of freedom: three in the shoulder, one in the elbow and three in the wrist, allowing great flexibility between movements; thus, the nervous system apparently must choose a particular motor solution each time it acts. Bernstein defined motor coordination as a means to overcome the indeterminacy due to the redundancy of the degrees of freedom for each given movement.

The variability of movement has a primary function for the coordinative structures that emerge under various types of conditions. The organism must be able to generate both stable (persistent) and flexible (variable) behaviors in response to changing intentions and dynamic environmental conditions (Davis et al, 2003). Motor creativity reflects an individual adaptability, which is original in relation to other adaptive solutions. It can be defined as new ways of acting adapted to new situations, it can be intra-individual or inter-individual.

At the intra-individual level, original and creative actions can emerge in practice as a consequence of the effort to improve performance, as we saw with the levels of creativity. The solution to the problem posed can be at the level of coordination of the task (a completely new movement as in the case of the fosbury flop) or at the level of movement control, that is, through movements that regulate the stability of a coordinative solution as when in a boulder through the attempts we gain coordination until we manage to solve it.

That is to say that the subject initially seeks a stable coordinative solution, which is then refined through practice in relation to the motor control of movement, that is to say that coordination is the function that conditions the available degrees of freedom of the system in a given time. movement in particular. Control refers to the parameterization of the topological relationships of the coordination patterns formed between the parts of the movement system (Orth et al, 2017). Both concepts are linked to each other. New solutions to a motor problem or challenge are discovered as new patterns of coordination and/or the way they are controlled.

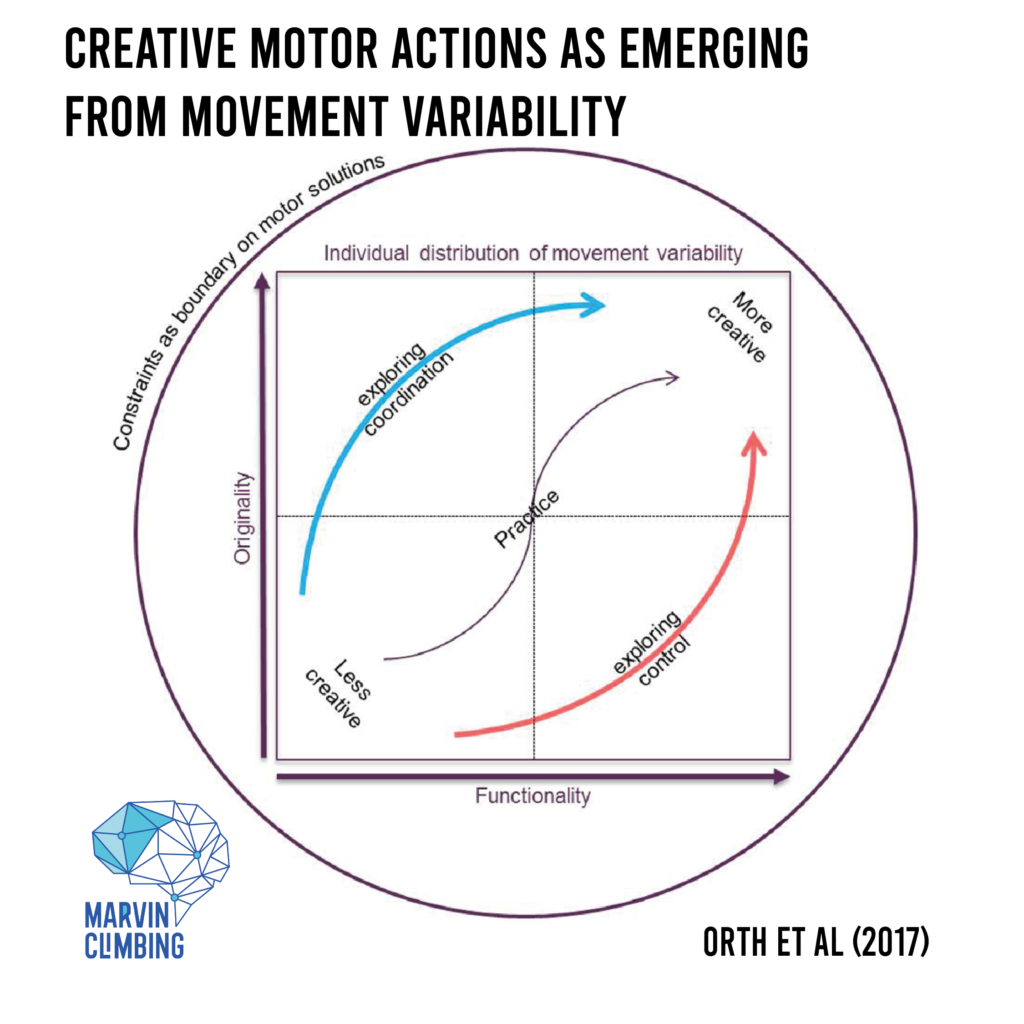

In the following figure from Orth et al (2017) we can see how exploration through practice can lead to new functional patterns that are represented through the two axes of both originality and functionality. Although this graph applies to the emergence of new creative solutions at the intra-individual level, it can also represent inter-individual solutions that lead to an innovation of a sport-specific technique.

The coach can encourage more or less variability by manipulating constraints during practice. In the case of climbing, during a session or training we can accommodate the distances of the holds and volumes, as well as their shapes to force through practice new movements at the level of coordination and mainly control in varied situations. . The best of all is that we can control it to the millimeter just by progressively varying the layout of the holds.

Inducing changes in this way has a significant influence on the stability or functionality of the coordination solution that requires transitions over different coordination patterns to maintain success.

The individual organization and (re)organization of the movement following a systematic manipulation of the environment, provides a vehicle to monitor how and when creative motor actions emerge and how flexible our athlete is in the face of changing situations.

Expert athletes are characterized by increased stability and at the same time flexibility of their coordination. They remain more stable in the face of disturbances than the untrained and at the same time are capable of finding new coordinations that more effectively and efficiently satisfy contextual changes, which in dynamic systems theory is called metastability (Balague and Torrents, 2011).

The acquisition of skills can be defined as the establishment of a functional relationship between the organism and the environment, characterized by the attunement to the relevant perceptual variables and the corresponding calibration of the actions in relation to the possibilities of each one. It results in the emergence of behavior that is adaptable to a wide range of performance contexts. It should not be considered as the acquisition of an internal state composed of different invariants of movement, but rather that it should be characterized by the refinement of the adaptation process, acquired by perceiving the key properties of the space that surrounds the medium of performance on the scale of the body of the individual and the possibilities of action (Araujo and Davids, 2011).

The contributions of the higher levels of creativity have their genesis in the lower level of creativity (Mini C). And this first level must be adequately stimulated, regardless of the level of the athlete, since the emergence of new movements at the coordination or control level will be part of the flexibility required to solve the most varied movements. The task of the teachers/coaches will be to modify the environment (route design in the case of climbing) allowing a space that encourages innovative and creative solutions. In this way we will open the door for higher levels of creativity.

References

Araújo, D., & Davids, K. (2011). What exactly is acquired during skill acquisition. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 18.

Balagué, N., & Torrents, C. (2011). Complejidad y deporte. Barcelona: Inde Publicaciones.

Beghetto, R.A., & Kaufman, J. (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for “mini-c” creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1, 73-79.

Davids, K., Glazier, P.S., Araújo, D., & Bartlett, R. (2003). Movement Systems as Dynamical Systems. Sports Medicine, 33, 245-260.

Hristovski, R., Davids, K., Passos, P., & Araújo, D. (2012). Sport Performance as a Domain of Creative Problem Solving for Self- Organizing Performer-Environment Systems. The Open Sports Sciences Journal, 5, 26-35.

Kaufman, J., & Beghetto, R.A. (2009). Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13, 1 – 12.

Orth, D., van der Kamp, J., Memmert, D., & Savelsbergh, G.J. (2017). Creative Motor Actions As Emerging from Movement Variability. Frontiers in Psychology, 8.

Ranganathan, R., Lee, M., & Newell, K.M. (2020). Repetition Without Repetition: Challenges in Understanding Behavioral Flexibility in Motor Skill. Frontiers in Psychology, 11.

Leave a Reply