According to Greek mythology, in the hills of Attica, lived an innkeeper named Procrustes, son of Poseidon. In his inn he offered lodging to solitary travelers. Once fed, he invited them to sleep in an iron bed and while they slept, he tied them by the hands and foot to the four corners. If the traveler was taller and his body longer than the bed, he proceeded to saw the protruding parts: feet, hands and head. On the other side, if the body was smaller than the bed, it proceeded to stretch it with hammer blows (hence its name: stretcher). It is said that it had two beds, one bigger and one smaller …

Procruste’s days ended when Theseus reversed the roles and invited him to check if his own body fit in the bed. When he lay down, Theseus tied him to the bed and tortured him there to adjust his body, hacking off his feet and head. Theseus continued his wanderings, coming to kill the Minotaur, the inhabitant of the labyrinth: “Will you believe it, Ariadne?” The Minotaur barely defended himself. ”(J. L. Borges).

Image of a vase of Theseus adjusting Procrustes (570-560 B.C.)

This myth has been used many times to explain some behaviors of the human being, such as the Procrustes syndrome, in which it is attempted to explain why those who, when overcome by the talent of others, decide to belittle them, even get rid of they. They have also found meanings in mathematics and computer science. Some theorize that Procrustes was the first serial killer (it’s a good idea for a Netflix series), but I want to refer to another meaning.

Procrustes’s bed could be understood as the measure of something to which we must necessarily adapt, either because we are too big or too small. By measure, in the field of training I understand the individual reality of each one, taking into account factors such as age, training history, years in sport, goals, level of practice, individual adaptive response of the loads, periodicity and continuity of training , history of injuries, etc. All these questions make individuality.

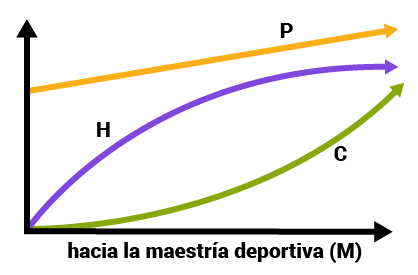

The process of sports improvement, according to Y. Verkhoshansky, depends on two factors: the increase in motor potential and the athlete’s ability to effectively harness that potential in training and competitions (or rock climbing). With the increase in sports mastery, more and more is taken out of your ability to work, so any progress will depend more and more on that increase in potential.

Training stimuli must accompany this ability to take advantage of this potential, in its fair measure, since if they are excessive it may happen that they skip stages or overtrains. Each mean and method that we use to train has a fair charge that produces improvements for each individual. Achieving the lowest load (optimum load) that produces the greatest improvements is essential: less is more, in reality, what is fair and necessary is more than any other combination. If we do other things, we advance steps, but we prevent generating adaptations with lower loads that will no longer serve us well. Skipping stages in the long run will be counterproductive.

I like to compare this process as a ladder, where each step serves to generate adaptations. When we skip one of those steps, we are losing the adaptive capacity of that step that we do not use, that is, we lose the option of an optimal workload. Lack of knowledge and lack of proper planning of loads, especially in youth populations where progress is generally very fast, since they assimilate loads quickly, risks putting a faster ceiling on the athlete’s life (which without a doubt that ceiling is potential). If the structures that are stressed are not contemplated, whether physical and physiological, such as tendons, growth cartilage, etc. and psychological, the problem may be greater, such as a limiting injury due to stress or overuse or the psychological burn out syndrome with the consequent abandonment of the activity.

The increase in epiphyseal fractures of growing fingers in adolescents in Europe is worrying, as demonstrated by one of the latest published studies (Lutter et al, 2020). This speaks of a poor (lousy) adequacy of the means and methods of training in this population, which should undoubtedly also be transferred to other populations that are not so at risk of this type of fracture. The following image (MRI) shows permanent damage to the growth cartilage of the interphalangeal joint of a climber (Schoffl, I and Schoffl V., 2016).

That is why, for each individual there is a unique and individualized load taking into account the specific context. The recipes that are found everywhere when looking for some training are like Procrustes’s bed, if we try to accommodate ourselves to them we should sacrifice in the best of cases the limbs and the head (if the bed is too small and we are left over for that load), without making great progress and staying out of injuries, or stretching our body by tearing the limbs to occupy the bed (with great risk of injury and / or overtraining) in the worst case.

It will always be advisable to look for a bed seller who understands, measures, evaluates and analyzes our dimensions and from there indicate which bed is the one that adapts to our real individual possibilities.

References:

C. Lutter, T. Tischer, T. Hotfiel, L. Frank, A. Enz, M. Simon, V. Schöffl. (2020). Current Trends in Sport Climbing Injuries after the Inclusion into the Olympic Program. Analysis of 633 Injuries within the years 2017/18. Muscle Ligaments and Tendon Journal. Nr 2020;10 (2):201-210

Schöffl, I., & Schöffl, V.R. (2016). Epiphyseal stress fractures in the fingers of adolescents: Biomechanics, Pathomechanism, and Risk factors.

Y. Verkhoshansky. (2002) Teoría y Metodología del Entrenamiento Deportivo. Ed. Paidotribo. Barcelona, España

Leave a Reply