In a small town surrounded by mountains lived a young man named Carlos, who was passionate about climbing. From a very young age, he dreamed of becoming a standout climber and representing his club in regional competitions. However, his path to success wasn’t as easy as he had imagined.

Carlos decided to take a risk and started training under the watchful eye of the club’s coach. Despite his dedication and effort, every time he tried to improve and keep up with his teammates, who often quickly solved the problems posed by the coach, he made mistakes, lost his balance, and frequently couldn’t find the right technique to link moves together.

Frustrated and discouraged, Carlos began to doubt his abilities and question his dream. One day, after another series of stumbles, the coach approached him with a reassuring smile.

“Carlos, I understand that you’re frustrated, but I want you to understand something crucial: failing doesn’t mean you’re doing something wrong. Failing is part of the learning process. Every mistake you make brings you one step closer to your goals,” the coach explained, with wisdom in his eyes.

Carlos, confused but willing to listen, nodded and allowed the coach to show him the importance of mistakes. He reminded Carlos that some of the world’s most successful climbers faced countless failures and defeats. They learned that understanding and learning from mistakes was essential to achieving excellence.

Over the weeks, the coach worked closely with Carlos. Every time he made a mistake, the coach provided guidance and encouragement. Together, they analyzed each mistake, identifying areas for improvement and adjusting Carlos’ technique. Gradually, Carlos began to change his perspective. Instead of seeing failure as an obstacle, he viewed it as an opportunity to learn and grow.

Finally, the day of the regional competition arrived. Although Carlos didn’t win, he showed significant improvement in his performance. The coach approached him with pride and said, “Remember, Carlos, success is not only measured by victories but by the ability to learn and overcome obstacles.”

Carlos understood that the path to success was full of challenges, but every mistake, every fall, was a valuable lesson. With a new mindset, he continued training with determination, knowing that the learning process never ends and that every step, even the mistakes and unsuccessful attempts, brought him closer to his dreams.

Most of the time in training, we encounter situations where we have to fail many times to find the right sequence and coordination for the movements to work. How many times have I left a session without completing a top, just like Carlos!

This is a delicate subject. If we are training and want to reach our maximum intensity, we have no choice but to fail. Intensity in climbing cannot be objectively quantifiable ; for each style, we will have an intensity, a complexity that will make something more or less difficult in relation to our capabilities.

When I meet my students, mainly young people, I see that training and failing in routes can be quite frustrating. That’s why it’s crucial to understand that failure is not the end of training but a learning strategy. It’s something we must use to our advantage.

Failing is part of the process, and the coach must design training sessions to ensure this happens. Without it, there would be no learning. The coach’s interventions are not intended to smooth the path of difficulties, nor to avoid errors, nor to provoke them, but to make the best use of them.

Error presupposes some prior application; there is no error when there is no action. Thus, we move from systematic error avoidance (learning as mastery of content) to its use as a teaching-learning strategy. Using error has pedagogical and psychological foundations and can also be explained in a biological context.

Every time we execute a movement and fail, the control structures of the movement are modified to improve the next execution, even in the same execution. Schmidt and Lee (2011) define two ways a person can make an error in achieving the goal of a task. One is a motor planning error, and the other is a motor execution error. Motor planning errors involve selecting a motor “program” that is inappropriate for the given situation. Correcting a planning error requires perceiving the error and selecting a new action plan.

In learning situations, the sensorimotor system predicts the sensory consequences (e.g., position and speed of the body or a limb) of the planned movement and compares this prediction with the actual sensory feedback of its execution. If there is no discrepancy, then the planned and executed movements are similar (although we know no movement is identical to another). If a difference is detected, it constitutes an error signal that informs how the movement failed (the error vector); for example, not reaching the next hold in a dynamic move, which leads to the correction of control for a future attempt.

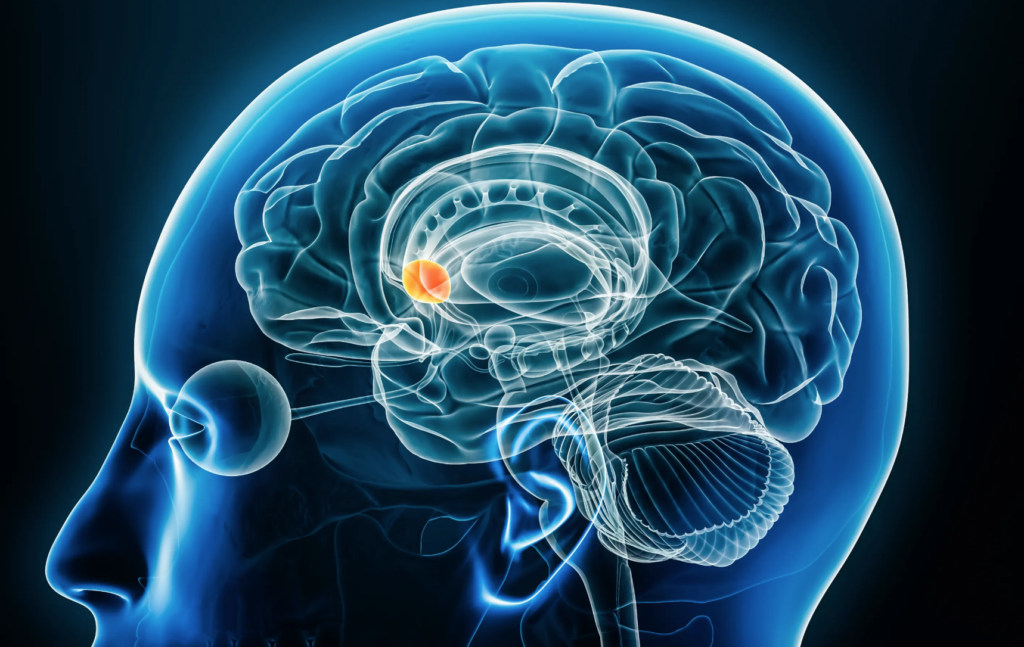

When movement execution improves, the error signal decreases, and thus, the error vector guides the learning process. Error-based learning is a powerful method leading to rapid acquisition of motor skills. Studies have shown that the cerebellum plays a crucial role in sensorimotor prediction and, therefore, in error-based learning. Plastic mechanisms that modify neural pathways between the cerebellum and the primary motor cortex are involved in learning.

When learning a new skill, the cerebellum is responsible for making precise adjustments in muscle activity and correcting errors in real-time. As more experience is gained in a task, the cerebellum helps automate movements and reduce the amount of attention required to perform the task. This process is guided by sensory feedback, mainly visual. If this is distorted, scarce, or nonexistent, the system can switch off cerebellar error-based learning and shift to reinforcement learning mechanisms mediated by the basal ganglia. However, the exact conditions and mechanisms of cerebellar and basal ganglia involvement in motor adaptation remain unknown.

The basal ganglia and dopamine play a significant role in motor learning. The basal ganglia consist of a set of neural nuclei in the brain that are critical for motor control and learning, while dopamine is a neurotransmitter released in the brain involved in regulating the reward system. Both are involved in habit formation and movement automation. When a movement is repeated multiple times, the basal ganglia can automate it, meaning it can be performed without conscious attention.

Dopamine is released in the basal ganglia when a successful movement occurs or when a reward is anticipated. This dopamine release helps strengthen the neural connections involved in the movement, facilitating the successful repetition of the movement in the future.

Dopamine is a key neurotransmitter in the brain’s reward system and plays an important role in motivation, learning, and decision-making. The prediction error theory suggests that dopamine release in the brain occurs when there is a discrepancy between an individual’s expectations and actual outcomes. This means that when an unexpected outcome occurs, more dopamine is released than when an expected outcome occurs.

The entire learning mechanism works because we want positive prediction errors (i.e., the reward is greater than expected) and dislike negative prediction errors. It seems to be some evolutionary mechanism that drives us to always want more and never want less (Schultz, 2016).

This substance acts as a neurochemical mechanism that reinforces or punishes behavior, thereby contributing to the learning process. But simply pairing a signal with a reward is not enough to learn; the outcome has to be surprising. In other words, the organism must detect a prediction error, a mismatch between the predicted and actual experience. This prediction error acts as a teaching signal to promote learning when needed.

The error learning theory is a conceptual framework used to explain how individuals learn from experience. The fundamental idea is that learning occurs when there is an error between what is expected and what actually happens. When an action or behavior leads to a different outcome than expected, an error occurs. This error acts as a signal to adjust future behaviors and improve prediction accuracy.

What needs to be done is to turn those errors into motivation for change, understanding that those errors are a reward and are fundamental to learning. The small achievements we obtain should be the source of motivation. Improving step by step, no matter how small, makes the reward of a positive prediction error work as reinforcement through the dopamine learning circuit.

But error is not an end in itself; it cannot be. Rather, it is a strategy. In this sense, error is part of the strategic vision of the coach/teacher. The use of error should be instrumental, not as a precise technique or strict guideline, but as a procedure or set of procedures that help us sequentially organize actions to achieve specific teaching goals.

References:

Schultz W. Dopamine reward prediction error coding. (2016). Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016 Mar;18(1):23-32.

Schmidt, RA.; Lee, TD. (2011). Motor control and learning: a behavioral emphasis. Human Kinetics; Champaign

Leave a Reply